The Space & Beyond Blog

The weird and wild moons of the solar system

As the moons of the solar system were discovered, astronomers became desperate to learn more about these strange natural satellites.

For millennia, nobody even knew if the Moon was the only moon of the solar system. However, our ancestors did recognize that the Moon was a sort of sibling to our planet. But what about the other moons of the solar system?

It wasn’t until early January in 1610 that Galileo Galilei set his novel telescope on Jupiter and tracked small points of light dancing around the gas giant. With these observations, Galileo finally revealed that Earth is not the only planet in the solar system with moons. (Some suggest German astronomer Simon Marius first noted Jupiter’s moons in late December 1609, just weeks before Galileo recorded his observations.)

The discovery of moons around another world left centuries’ worth of astronomers desperate to learn more about what other natural satellites the solar system holds. And now, increasingly powerful telescopes and interplanetary spacecraft have revealed that many of the moons in the solar system are far stranger than anyone could have imagined.

So, let’s take a look at the weird and wild moons of the solar system — one planet at a time.

MERCURY

Nope. No moons.

Venus

Nope. No moons.

The Earth

The Moon

The Moon transiting in front of Earth on July 16, 2015, seen from DSCOVR. Credit: NASA

Earth’s Moon isn’t the largest moon of the solar system— not by a long shot. The Moon comes in at number 5 on the list of largest moons, between Io and Europa (two of Jupiter’s moons). However, at about 2,150 miles (3,400 kilometers) in diameter, the Moon is still larger than Mercury.

Mars

Phobos and Deimos

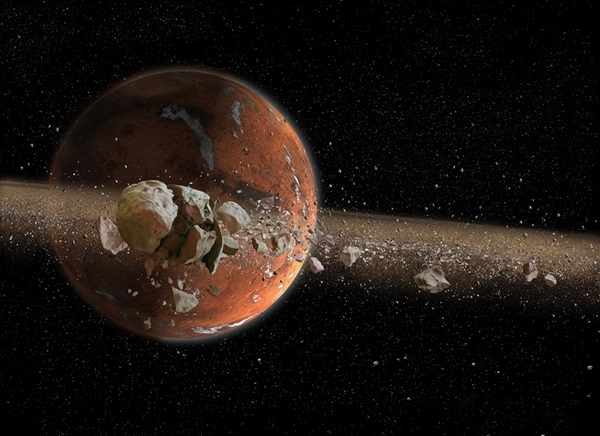

Someday, Mars’ moon Phobos will slip past a certain point in its degrading orbit and get ripped apart by tidal forces, forming a ring. This illustration depicts Phobos midway through that process, overlooking the Red Planet. Astronomy: Ron Miller

For a long time after their discovery in 1877, scientists assumed Mars’ two puny moons — Deimos and Phobos — were captured asteroids. But then, evidence revealed that both moons formed at the same time as the Red Planet itself, and that the smaller one, Deimos, has a mysteriously tilted orbit. Now, many think that Mars’ moons formed out of debris ejected when a giant impactor struck Mars between 100 million and 800 million years after the planet’s creation.

Furthermore, a new theory suggests that ever since the original collision, generations of martian moons have been recycled into rings, which, in turn, were molded into new, smaller moons of the solar system. And that moon-ring cycle will likely continue for millions of years to come.

Jupiter

Titan, Enceladus, and 80 more

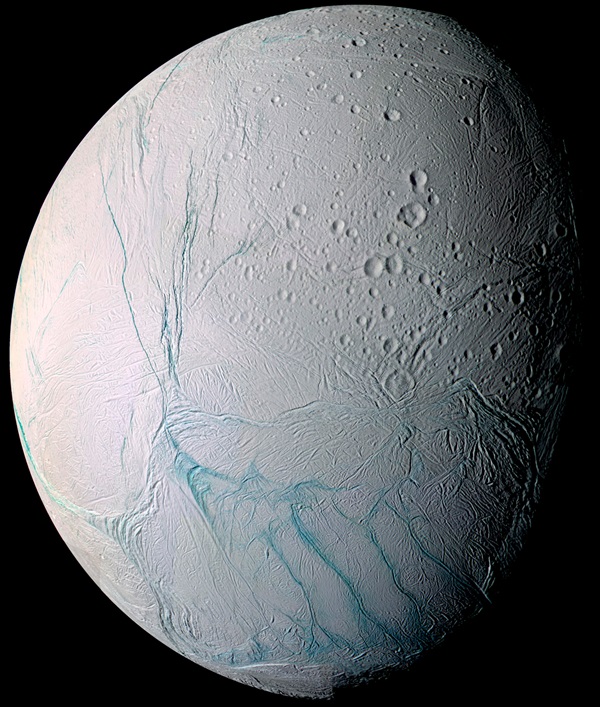

Enceladus appears covered in craters and cracks in this enhanced-color mosaic. This stunning world of ice and geysers orbits Saturn in 32.9 Earth hours. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Saturn usually gets credit for its rings, but its many moons are just as fascinating. First and foremost is Saturn’s largest moon: Titan. In addition to harboring an underground liquid ocean, this great moon of the solar system is the only world besides Earth confirmed to have an active rain cycle. Furthermore, its opaque nitrogen-methane cocoon is the second-densest atmosphere among all the solid bodies of the solar system, after Venus. Such a thick, insulating atmosphere sustains frigid surface temperatures of –290 degrees Fahrenheit.

Still, these chilly temperatures are much warmer than the moon’s smaller yet equally fascinating sibling Enceladus, which is largely made of water ice and covered in intriguing features. Decades ago, Voyager 2 photographed Enceladus’ craters, narrow valleys, and expanses of grooves and ridges. It spotted sharp-edged canyons up to 120 miles (190 km) long, 5 miles (8 km) wide, and 0.5 mile (0.8k m) deep fracturing the moon’s surface.

Enjoying our blog?

Check out the Space & Beyond Box: our space-themed subscription box!

Uranus

Titania, Oberon and 25 more

Uranus’ largest moon, Titania, is seen in this composite created from images captured by the Voyager 2 spacecraft as it made its closest approach to Uranus in January 1986. Credit: NASA/JPL

Discovered in 1781, Uranus is an ice giant orbiting our Sun once every 84 Earth years. This mysterious world, which appears as just a tiny dot in most amateur telescopes, not only possesses a system of thin, faint rings, but also 27 moons (by our current count).

The largest uranian moon is aptly named Titania, which was discovered just six years after the planet it orbits. When Voyager 2 passed by this world, it found signs that the moon was geologically active, evidenced by features like an expansive system of fault valleys stretching some 1,000 miles (1,600 km) across the moon’s surface. And like Titania’s slightly smaller brother, Oberon, Uranus’ moons are made of roughly equal parts rock and ice.

Neptune

Triton, and 13 more

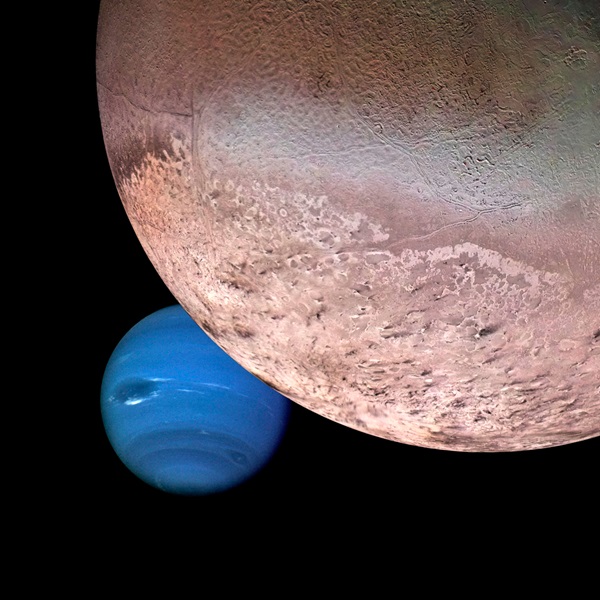

This computer-generated montage shows Neptune as it would appear from a spacecraft approaching Triton, the planet’s largest moon. Credit: NASA/JPL/USGS

Triton is not only the most distant of the solar system’s major moons — those at least 1,500 miles (2,400 km) in diameter — but also one of the weirdest moons of our solar system. To begin, even though Triton is enormous and enjoys a perfectly circular orbit, Triton flies around Neptune backward. Triton is also one of just a handful of objects that harbors active, ongoing eruptions. And like Saturn’s moon Enceladus, the cryovolcanic material vented from below Triton’s surface is not hot, but cold. Lastly, Triton looks like a cantaloupe. Bizarre depressions and fissures each 20 miles (30km) across dominate its western hemisphere. We call it “cantaloupe terrain” because it perfectly resembles the skin of that tasty melon.

So, with nitrogen geysers, volcanoes of water ammonia, a cantaloupe surface, and a backward orbit, Triton definitely fits the bill for one of the weirdest and wildest moons of our solar system.